Grids are Good

Observations from a morning detour

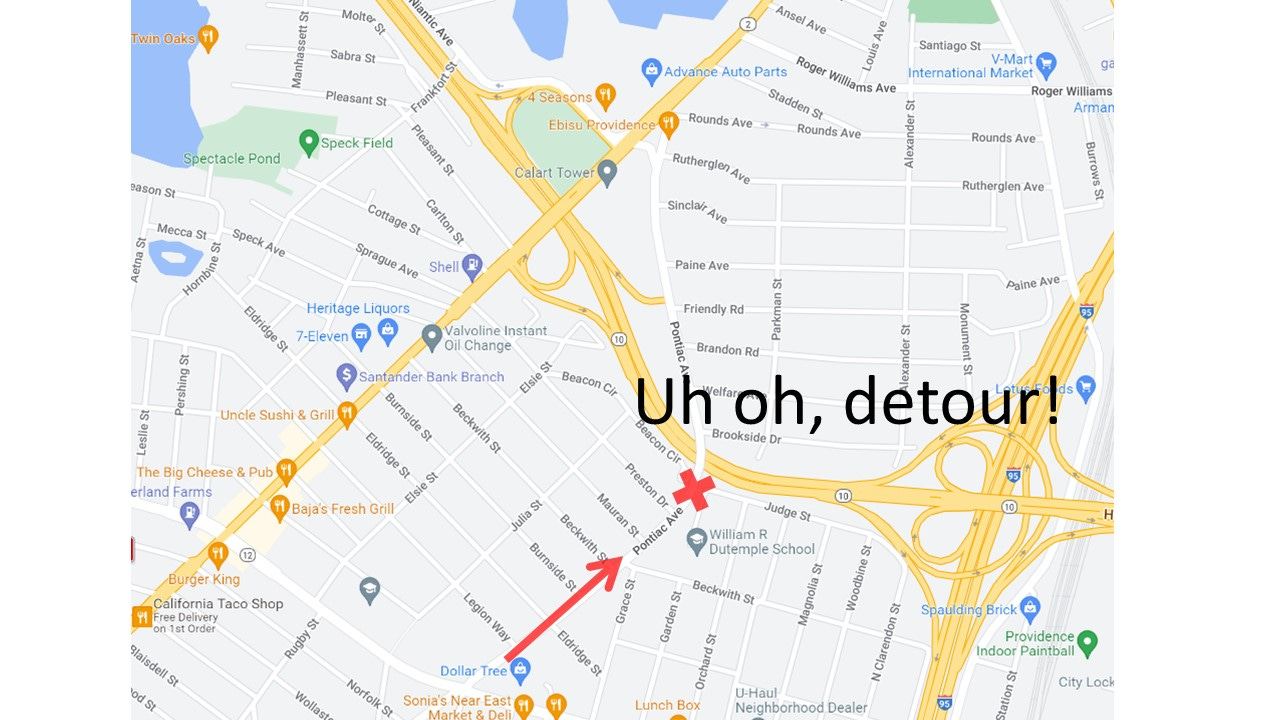

On a recent weekday morning, I was driving up Pontiac Avenue in Cranston, Rhode Island, on the way from dropping my son off at daycare and headed to my daughter’s kindergarten. Just as we came to the intersection where Pontiac Ave crosses over Rt. 10 (a sort of inner-beltway-to-nowhere built during the highway-building bonanza of the mid 20th century), we came to a police cruiser and detour sign. More utility work going on in the street up ahead it seemed–no biggie, detour time!

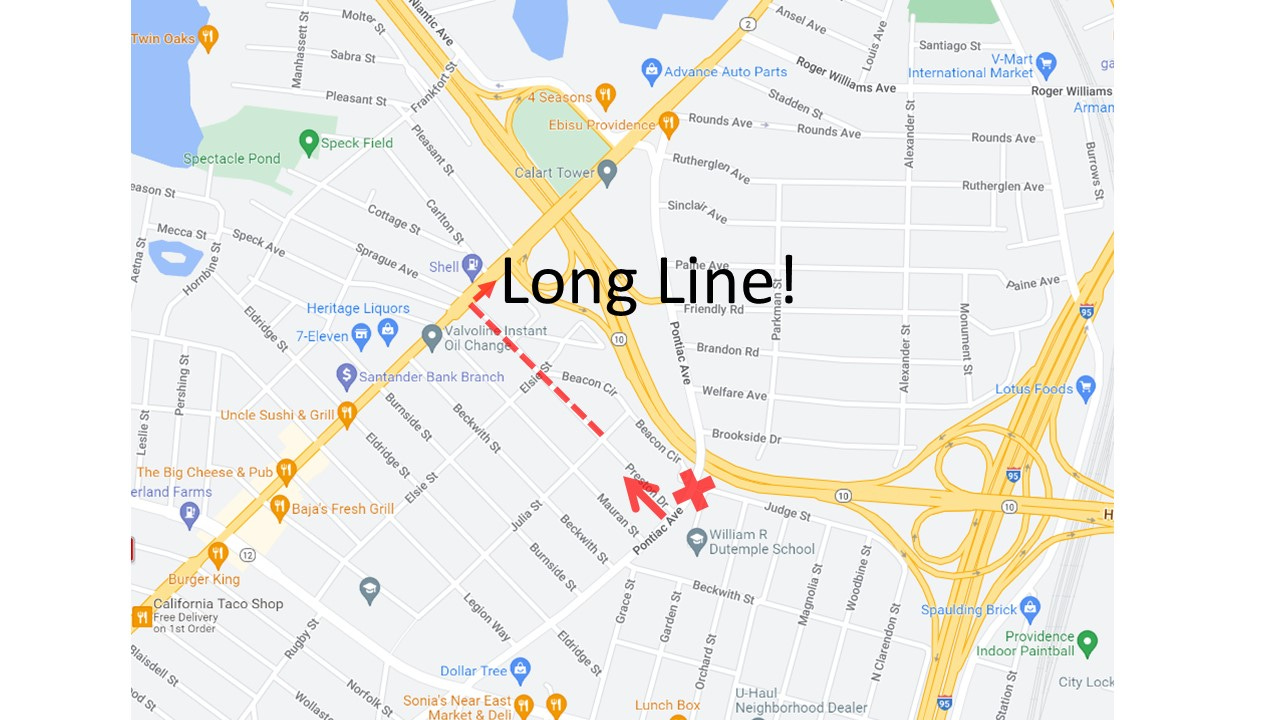

I turned left into the residential neighborhood to get to the next road that crosses Rt. 10, Reservoir Ave. (“major arterial” in engineer speak). As I turn, I realize that the line of cars ahead of me from this same detour is several blocks long and not moving, as everyone tries to make the right hand turn onto busy Reservoir--uh oh, do I need to start worrying about being late to drop off my daughter at school?

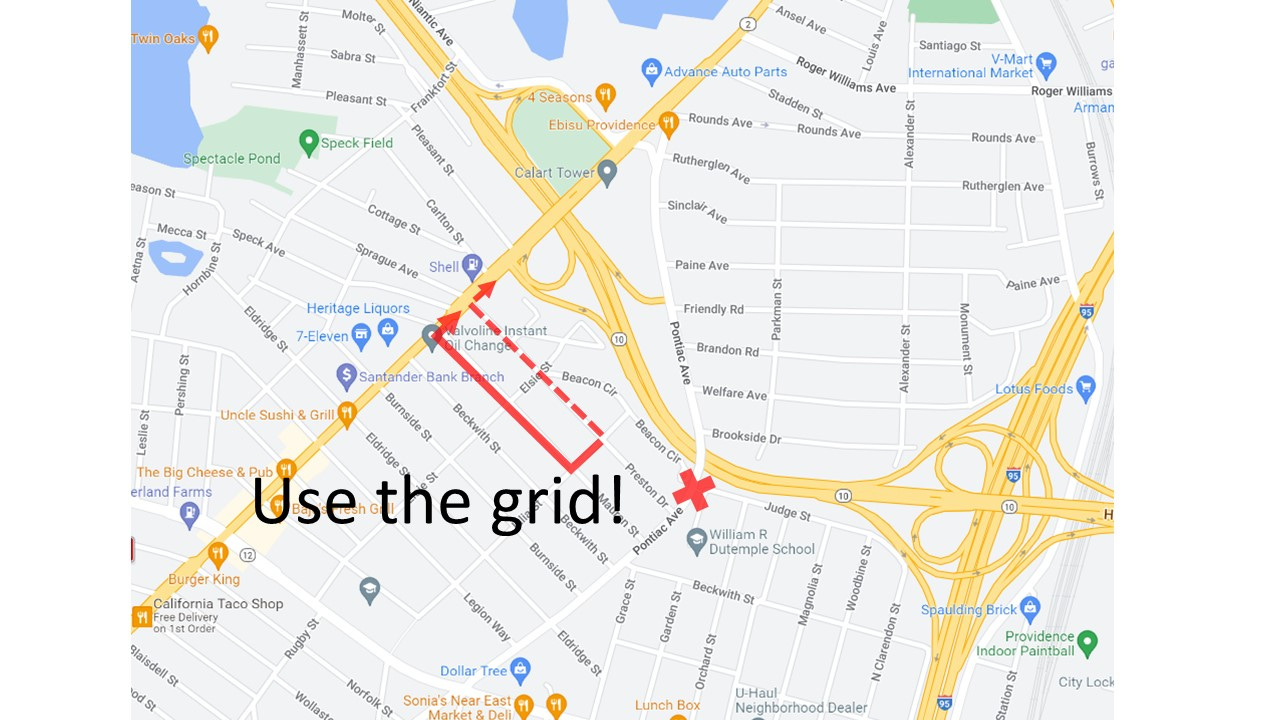

Now fortunately this little neighborhood of post-war detached ranches and bungalows is laid out on a grid. So I take a quick dog leg to the left and approach Reservoir on Mauran St.–no line at all. I suppose you might say I cut the line. But I’d prefer to say that I used the grid that our ancestors bequeathed to us to do what grids are so great for: they are redundant and distributed.

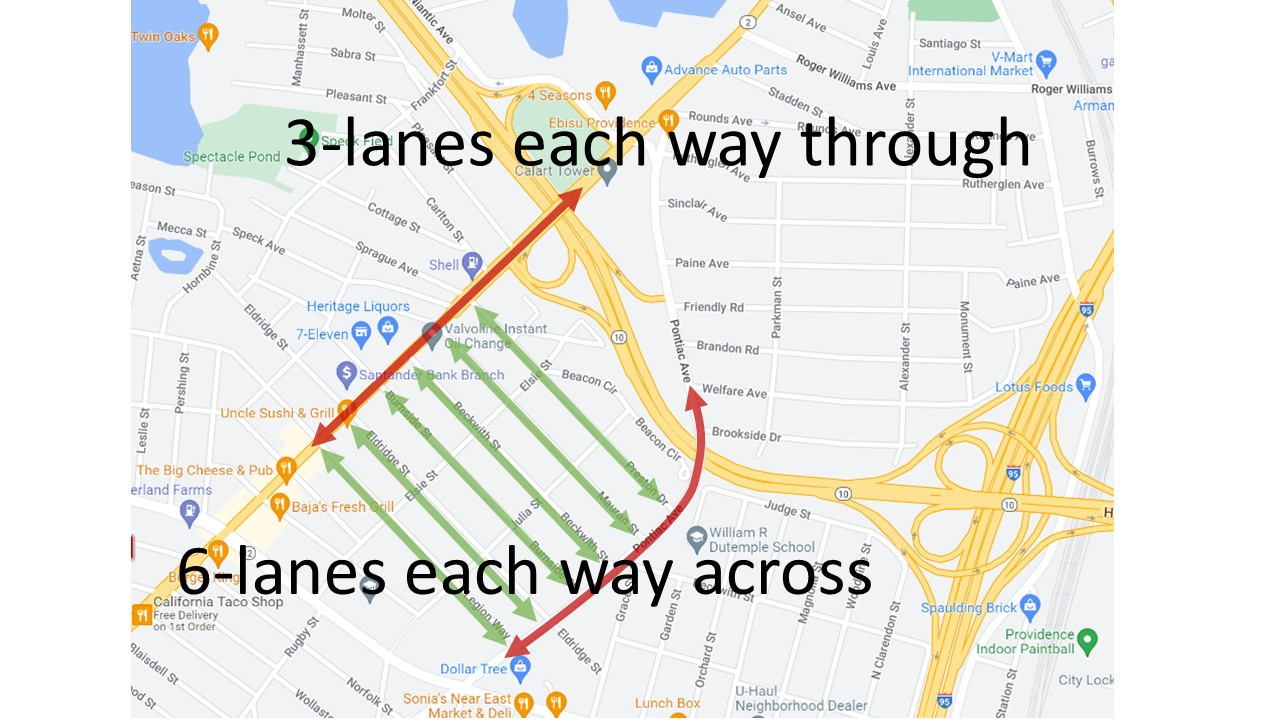

Grids are Great! If one road is blocked on a gridded set of streets, you can go one block over and find another way through. Grids are easy to understand, even for visitors. There are dozens of paths between point A and point B, allowing each driver (or person walking or biking) to optimize their own route based on their preferences and current conditions. There are also a TON of lanes available–for driving, and for queuing at intersections. This little section of gridded streets has a total of six lanes, each way, going north-west to south-east. In contrast the “major arterials” on each side have a total of three lanes going each way. The neighborhood side streets have double the capacity of the major streets!

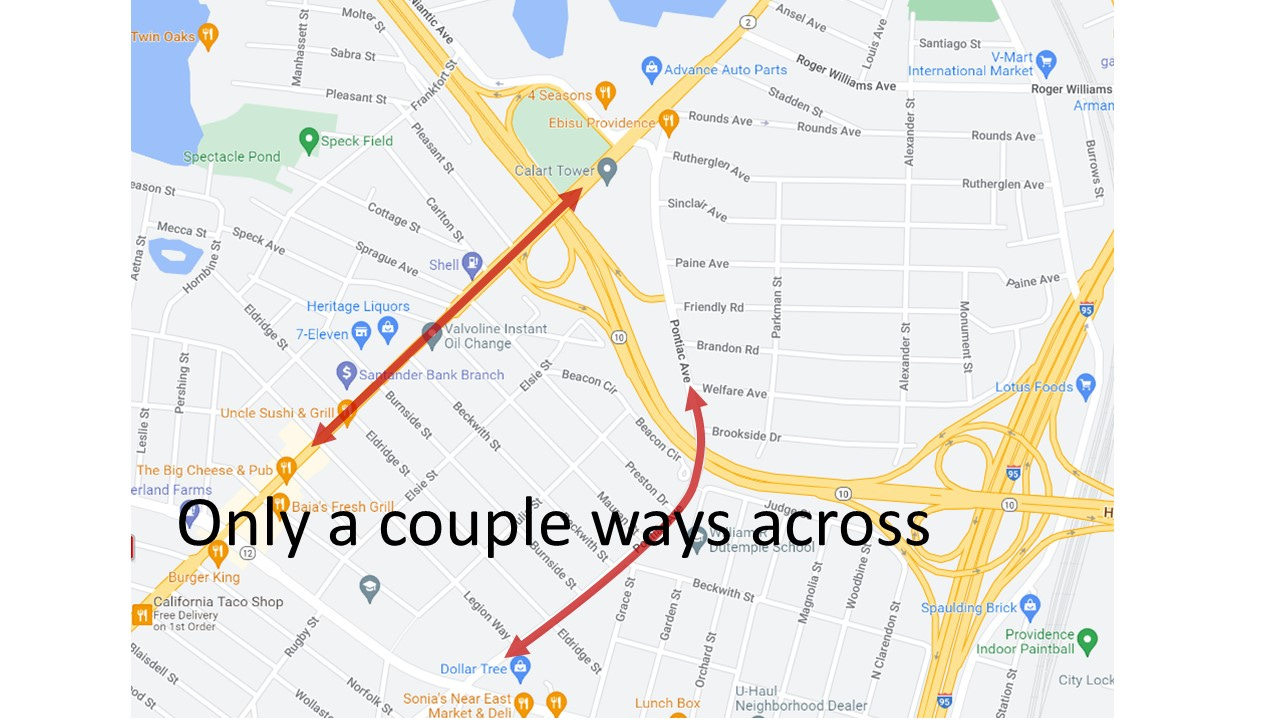

Now grids can’t go on forever (looking at you Public Land Survey System). They eventually run into geographic constraints–the ocean, rivers, cliffs, etc., or man-made constraints: city walls, railroads, and… highways. See, the big problem I was experiencing is that there are only a few ways across the highway I needed to get over. These bridges become choke points for the thick web of streets on either side. Highway’s are like rivers–easy to travel down, hard to cross.

When you start to see the streets as a network of little streams, it’s easy to see what causes the worst congestion. When many lanes dump into few lanes, you get congestion. Building bigger and wider roads doesn't solve the problem, doing so can also destroy the value of the land on either side of the road (by taking property to widen a road or making a street less attractive to be on). But here the humble street grid steps in: a network of lots of little, normal streets can carry both a ton of traffic (and provide for a robust canopy of street trees), and is resilient to local failures (or utility-work detours).

The neighborhoods, in general, favor grids for pedestrians and bicycles, but oppose them for automobiles, wanting to confine through traffic to arterials. This is, I understand, called “woonerf”.